Readers, if you weren’t there on Monday for the discussion on Service of Process and Taking of Evidence Abroad, you missed a very interesting and engaging discussion. There were some dramatic moments, or dramatic at least if international judicial assistance is your thing. Noëlle Lenoir gave a forceful presentation of the traditional French position about the relationship between French and EU views and American views on the Evidence Convention, and in particular e-discovery and document discovery generally. Chuck Kotuby, who is handling some litigation against the government of Kazakhstan, put up a map showing global corruption levels that had Kazakhstan in bright red, while a represenative of the Kazakh government was sharing the stage with him.

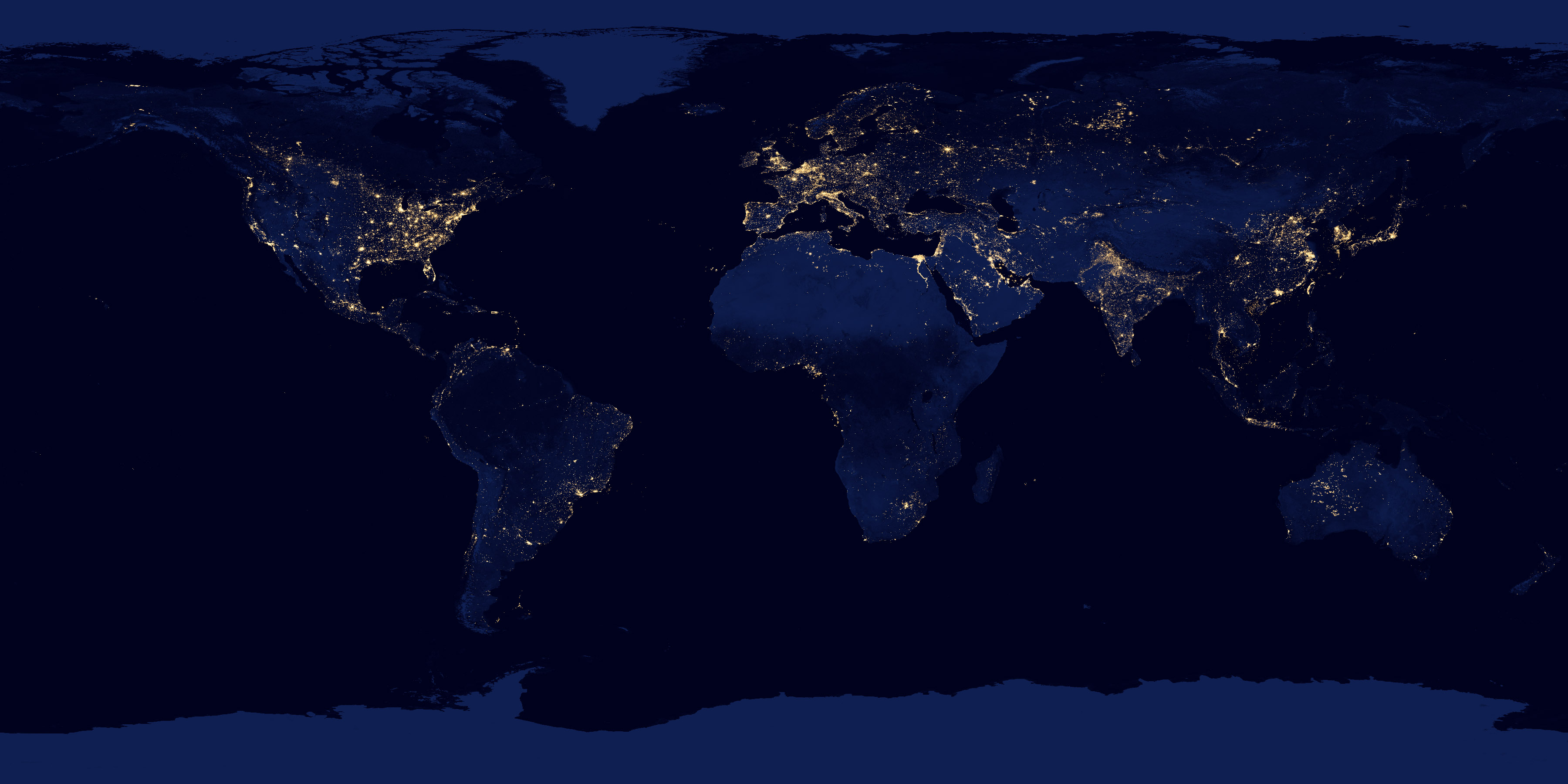

Some of the presentations were particularly illuminating and informative. I would call out three in particular that I thought were especially terrific. First, Roland Portmann, a legal advisor and Second Secretary for Political and Economic Affairs at the Swiss Embassy, gave the best explanation I have heard for the why behind the Swiss approach to taking of evidence on its territory. He suggested—and this is my interpretation of his message, maybe not his—that “sovereignty” in this context is really a proxy for “privacy.” In any procedure for the taking of evidence in Switzerland, the need for the evidence in the litigation gets balanced against the privacy interests of the witness, and the Swiss believe it is necessary that a judge be the one to undertake the balancing analysis. Second, Alex Blumrosen, an American lawyer who has practiced in Paris for decades and who was my partner in crime on the ITechLaw delegation to the 2014 Special Commission meeting, gave a wonderful practical outline on the use of Chapter 2 of the Evidence Convention in France. If you have a big case and need sophisticated advice on obtaining evidence from a French firm or witness, call Alex. Last, David Bowker of WilmerHale had a really insightful comparison. He compared the map of membership in the Service and Evidence Conventions with a NASA map showing the earth at night from space. The Conventions are in force, more or less, in the places where “the lights are on,” which is to say that the Hague Conference has its work cut out for it in much of Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, and parts of the Pacific region. Here are the images (I don’t have the Convention membership map handy, so I am using the Hague Conference membership, which can stand in as a proxy).

Now let met turn to my own contribution to the event. I suggested that the Special Commission should be more explicit in its conclusions and recommendations on issues of construction of the Convention, so as to help courts avoid bad decisions, particularly in cases where the court is frustrated by a defendant ducking service, or a foreign central authority enabling a defendant to duck service. I gave an example of a case in which the C&Rs actually did provide guidance to US courts that led to a correct decision despite some erroneous US precedent, namely New York State Thruway Auth. v. Fenech, which cited the C&Rs in holding, despite bad precedent to the contrary, that Article 10(a) does permits service by postal channels. And I gave an example of an area where I thought the Special Commission’s clear guidance was likely to lead to good decisions in the future, namely the use of video technology under the Evidence Convention. Then I turned to an area where the lack of express guidance may have contributed to bad decisions.

“Bad decisions?” you say. “Tell me more!” Thank you for asking.

If the Georgetown event was any indication, very few American lawyers seem to agree with me that service via email is not permissible under the Service Convention when the Convention applies. On the one hand, this could be just confirmation of the hypothesis I put forward in my presentation—when foreign defendants or central authorities put obstacles in the way of service through the main channel, judges get frustrated and authorize service by means that the Convention doesn’t permit so as to ensure that you can’t avoid litigation by ducking service. I get that. But I am 100% certain—well, 99% certain, anyway—that my reading of the Convention on this point is correct. I’ve done this before many times, but here are the points of my argument:

- The Convention is exclusive. When it is necessary to transmit a document for service abroad, you must use one of the methods the Convention authorizes or permits. This is the holding of the Volkswagen case and the consensus of the Special Commission.

- Leaving aside Article 19, the only provision in the Convention that could arguably permit service of process by email from the plaintiff direct to the defendant is Article 10(a). But in Gurung v. Malhotra, the source of the line of bad cases, the defendant was to be served in India, which has objected to service by postal channels. So in such countries there is no provision of the Convention that authorizes or permits service by email.

- In countries without an Article 10(a) objection, I am open to the argument that email should be considered part of the postal channel, though I think that argument is wrong for the reasons I gave in my 2013 paper, modestly titled Gurung v. Malhotra is Wrongly Decided.

- While a court can authorize service by alternate means that violate a foreign state’s law, it cannot, under FRCP 4(f)(3), authorize service by alternate means prohibited by the Convention. That’s written right into the text of the rule.

I think you could engage in some clever argument aimed at showing that when you send an email, you are not actually, or at least not necessarily, transmitting a document for service abroad. For example, suppose the defendant in India has a Gmail account. What happens when I send the email? My server sends the data to a Gmail server, perhaps located in the United States, via SMTP. The defendant, perhaps, then retrieves the email from the Gmail server via another protocol like IMAP or POP3, or even HTTP if the defendant is using webmail. But I think this doesn’t work for several reasons, some practical and some doctrinal. As a practical matter, it is very difficult to map out the IT infrastructure a particular defendant is using. As an doctrinal matter, it is very difficult to believe that a state that objected to service by postal channels in its territory, say, would have agreed, when it signed the Convention, to service on persons in its territory by email provided the email was sent to a server outside its territory but then retrieved by the defendant in its territory.

My challenge to you, readers, is to tell me why this is wrong!

Leave a Reply